On Mobility, Rituals, and Senses – Post- and Transnational Explorations — An interview with Marta Keil

Marta Keil is a performing arts curator and researcher who co-runs the Performing Arts Institute in Warsaw, Poland. She has collaborated as a curator and dramaturge with a number of artists and works on a regular basis in a curatorial tandem with Grzegorz Reske (ResKeil). She is also the editor of several publications on performance and politics. She has been the facilitator of the Transnational/Postnational Artistic Practices trajectory in RESHAPE, which engaged with questions of imagining an artworld ‘after the national’, starting from the broader notion of the political map and how it affects cultural practices. In this interview, she spoke to us from Warsaw, about some of the processes and outputs of her trajectory within RESHAPE.

[Lina Attalah] How was the question of transnationality/postnationality addressed in your first encounters? I saw in the documentation that mobility was central to the conversation. But I was also wondering how the question was tackled in relation to the modern nation state, as also a form of affinity, as a home?

[Marta Keil] I recall from the first conversations that the notions of transnationality and postnationality were challenging for us all. What we realised during our first workshop and following meetings is that we tended to avoid them. Instead, we brought to the table the urgencies we all felt with regard to the project, which were often the very reason why the participants decided to apply. And these urgencies were quite diverse, as they related directly to the variety of contexts we were coming from.

As the time flew by, we actually felt even more perplexed about the transnational and the postnational. Both notions seem pretty utopian and we did not know how to imagine them together, as there is no universal form of utopia, that would work for everybody all the time, regardless of context. So indeed, no matter how much we would love to imagine a reality in the arts field as postnational, we all experienced on many different layers the restrictions of current nation-state structures, which are restraining mobility from one country to the other in some cases, forcing mobility in other instances.

For many of us, the materiality of national and geopolitical borders is an everyday experience. Visa regulations, the complicated procedures to obtain them, the recurring uncertainty each time you apply, unexplained refusals to give the visa, cancelled performances, courses, artistic and educational projects, no access to the diversity of perspectives, interrupted flow of thoughts and inspirations, economic discrepancies limiting travel, isolation. These are real obstacles that one will encounter sooner or later while working in the international field. The consequences and limitations resulting from a given geo-political situation have become even more tangible recently, now that populist or purely nationalist governments have come to power in many countries. So the postnational seemed to us very far away from the actual reality, no matter how much we would desire it to be true.

Actually, the question of postnationality and transnationality was so present in the 1990s, with the promise of a new, global world that would become flat and horizontal. From my own experience, coming from Eastern Europe, I remember the joy of the idea that the borders would finally open, only to realise later that they did open, indeed, but just for some of us and in some contexts only.

Nevertheless, at some point in our trajectory we tried to imagine a situation where we could function with the understanding that national borders weren’t an obstacle. We tried to free the imagination and at least sketch some possible ways of working even if they were utopian ones. We were asking: what if the borders didn’t exist? What if we could get rid of geopolitical, postcolonial restrictions? What could that shift of perspective bring? But we were very careful not to go too far into the imaginative, because that would carry the risk of forgetting the reality of the existing restrictions. What we attempted to do instead was to imagine how ‘feeling at home’ is possible outside of modern nation state frames; how can an artistic practice be rooted in a given local context while the working conditions require a constant mobility?

[LA] To what extent did the political context of Europe, with Brexit, rising racist sentiments and so on, permeate the conversation?

[MK] A lot: rising racist, nationalist, misogynist and homophobic tendencies, especially in these past two years, 2019 and 2020. These had a huge impact on our discussions. During the project, Brexit happened, governments in some Eastern European countries had been gradually turning into nationalism and homophobia; Catalonia struggled to redefine its position within Spain; there were repeated acts of racism in Brussels; several attempts to introduce a complete ban on abortion in Poland, and many more. All of this forced us to redefine the situation we were in. But also to find a common ground for a group composed of practitioners bringing such a multiplicity of experiences, needs, and contexts was a challenging task. We might have many similar ideas, but often the ways of understanding them differed. We needed to build at least a basic trust and had to try to find common definitions of notions that we wanted to apply to the conversations. The RESHAPE framework grouped people together who might not necessarily meet or work with each other otherwise – which was one of the strongest elements of the project, but also one of its biggest challenges. Building a common ground in this case required a lot of time, focus, patience, and emotional support. To me the very working process is a main prototype of the RESHAPE project.

[LA] I am intrigued by your choice to integrate the idea of sharing rituals as one of the activities within your trajectory. I was wondering how you got there in the context of your discussions on postnationality and transnationality. I also saw that you have been thinking of rituals in terms of rooting and healing, with actions such as collective writing. What were the manifestations of rituals in your trajectory?

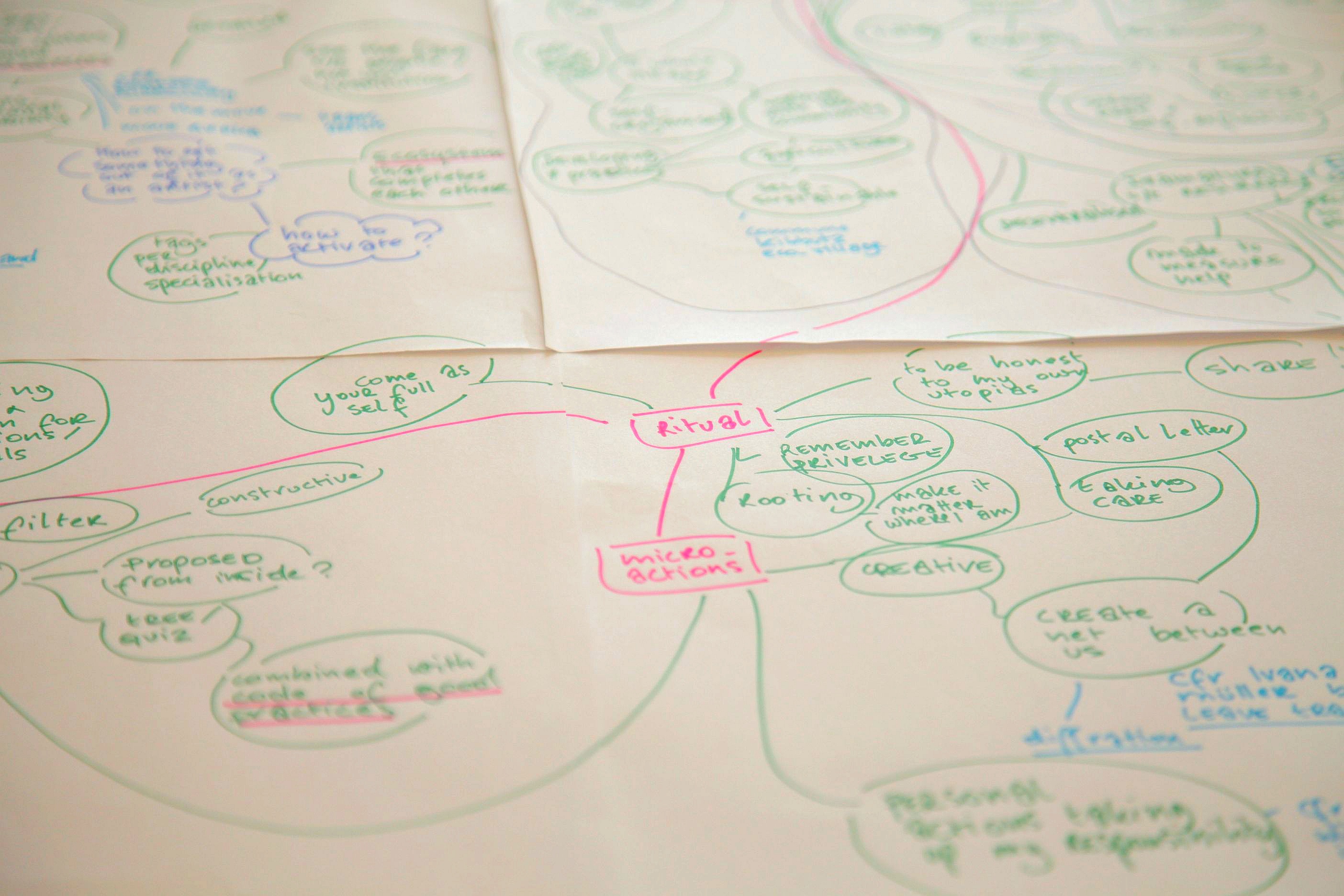

[MK] The very first idea of the rituals came from the attempt to get to know each other and to build a common ground between us. It came to us in a conversation as a proposal from Reshapers Ingrid Vranken and Petr Dlouhy in the first workshop we held. It landed well, even though for some of us, myself included, it was a new approach.

We set up a game, where the task was that everyone proposed a ritual to someone else. We were then experiencing the rituals individually and giving each other feedback. One of the participants proposed to another to observe a plant in their setting, in their flat or nearby park, and to share these observations. Another one proposed a book to a fellow participant and to take it always with them on travels, reading one page a day in new places. These were both exercises of embodying someone else’s perspective in your everyday routine.

In some cases, the rituals took place for weeks; in others, they didn’t happen at all because some didn’t have time or some didn’t accept the ritual proposed to them. Nevertheless, this experience, including all the diversity of perspectives, became a way to understand each other better and to see in practice what type of collaboration we were comfortable in.

The main idea was to understand the politicality of the ritual, as a way to influence the everyday space, and as a way to shift the focus, to change what we see and how we perceive it, to kind of reset the mindset. The rituals were working here as a tool that could help to establish relations between participants from various contexts and backgrounds – a tool that opens up a dialogue or rather builds a condition of listening to each other. Sometimes a ritual can be much more effective here than reading dozens of books, as it allows learning by doing and opens up multiple ways of generating and transferring knowledge. I strongly believe in the politicality of poetics.

What was crucial was the regularity and the routine of the rituals, as we realised transnational connections could be built on a horizontal level, as something embedded in the everyday practice. We also know now that rituals can hardly work as a political tool if they are not rooted in a given local context.

The rituals game also gave us a chance to get in touch between our meetings and build links within the group outside of the gatherings’ framework. It helped us a lot when the pandemic broke out, which cut off all the physical meetings in the middle of the project.

[LA] I also saw that you developed another tool, namely to place the rituals into some sort of a grid that is interconnected and acts as an instrument of learning more about each other but also doing some unlearning. Can you talk to us about the grid and how your group developed it?

[MK] The grid was one of the first ideas we had and it was related to our experiences as art workers. It came from the sense that among artists, organisers, producers, researchers, curators, and institutions, there is this lack of being able to listen to each other. How to listen to each other with ears open for a diversity of contexts? How to avoid copy-paste solutions? How to get rid of our own presumptions and stop being occupied with ourselves for a moment? Rituals are very helpful here again as they help to practice patience and various ways of listening.

The grid was a proposition to institutions that organise our everyday life in the art world, to pause for a moment and reflect on how they operate. To a certain extent it was thought of as an evaluation tool, but not in the sense of evaluating a particular action or project, but reflecting the very working methods. It was a tool that aimed at shifting the focus from what is being produced to how it is being done. The way of working is one of the most crucial things to be addressed but there is never enough time. In the rush for new projects and new ideas, it is the last field to reflect on and is always left aside, for a moment, when the time will come, and it never does.

We proposed the grid as a game and we started to develop it by elaborating the questions we wanted to ask. Then the idea transformed into a form of the tarot cards, which finally became one of our prototypes.

[LA] The tarot cards is a shared prototype with the Fair Governance Models trajectory, right?

[MK] Yes, although both groups address it from slightly different perspectives. There is a whole deck of 22 cards. We decided to split it half-half between the groups. Although within the trajectories we were working with different topics, at some point we realised our work complemented each other. We both realised we needed a new framework to reflect relationships and constellations within the arts field and beyond. What we proposed was to inscribe certain rituals in the cards, as well as the questions we have been elaborating since we started to work on the grid.

For example, let’s take the card ‘The Fool’, that we decided to rename as ‘The Traveller’ and relate it to the sense of place. We decided to propose to read the card as an invitation to reflect on the journey of personal growth in relation with mobility. What abilities does mobility give away? What are the problems of mobility? What are the clichés associated with it? What do we see through mobility, and what remains unseen, unheard, and inaudible for us? It was a way to address the very core of the political question of mobility: who is able to travel, who is allowed, who is visible thanks to their mobility, who has the privilege to move freely and who is forced to move? Referring to the particular context I come from, there is also the question of who has to be mobile in the current circumstances of their own country that don’t allow them to continue their work. There is also the question of how to be mobile while staying rooted in the local ground and having a real political impact on the situation you are in. So how can you pass on what you receive when you are able to move? How not to transform your mobility into a process of exotisation, of using the other in order to get rid of your own context? How can travelling be connected to the sense of home and homemaking?

[LA] There was an interest in developing a repository of references on mobility and monoculture in your group. Can you tell us, off the top of your head, what these references were? What were inspirations for this repository?

[MK] When it comes to monoculture, homemaking, and hypermobility, one of the really important resources we followed was the actual embodied experience of many of us. The other resources were the research on mobility in the arts, that has been conducted by organisations such as On the Move, IETM, Flanders Arts Institute (especially the project Reframing The International), Nomad Dance Academy, i-Portunus, L’Internationale network and many others. Another important resource of knowledge was a broad research on artistic residencies, which is ongoing mainly in the visual arts field, but not only there. But first and foremost, there was a unique level of expertise in the group itself. Some of the trajectory participants, such as Martinka Bobrikova, Oscar de Carmen, and Pau Cata are actively involved in the research on new, alternative models of artistic residencies and mobility, while Marine Thévenet and Heba El Cheikh practice and reflect various models of organising and fair governing in the field, also on the transnational level.

We also carefully followed the reflections on the ecological impact of hypermobility in the art world. We were trying to understand whether getting in touch is possible without abusing all the environmental resources we have. Can we travel slower or more consciously? We referred to thinkers such as Michael Marder. One of the group members, Dominika Święcicka, did a research about the complexity of procedures to get a visa for artists, rising awareness of these restrictions in many organisations she talked to.

While reflecting on the figures of host and guest, we were also referring often to thinkers such as Sarah Ahmed, who wrote on the notion of home making.

[LA] Part of your trajectory, as you said, had some research ideas that included interviews on inclusion, access to visas, and so on. Can you tell us what has been done in this research?

[MK] Dominika Święcicka started a series of interviews with artists about access to visas, but then she observed that artists who had met with many difficulties in order to move to certain places were extremely tired of talking about it. She felt it was high time to talk to these particular artists about their work, not about how they got to where they were. On top of that, there are many initiatives that are dealing with this problematic already, for example On the Move. It seemed the research on visas is so complex that it could become almost a separate project, done in collaboration with the organisations that have a huge expertise to share. Dominika’s crucial observation was that the accessibility of information and of the procedural language would be especially important in this case, and she has an idea to continue her work in this direction.

[LA] Your trajectory’s idea of ‘sensing the journey’ is very interesting, as it reflects how concepts need to be fed with sentient elements in order to be properly engaged. How did this sensory sensibility come about and how was it embodied and translated into your prototypes?

[MK] The idea came from the rituals experience and from the survey results that we made among the RESHAPE constellation of people, asking them about their experience with hypermobility. When collecting the survey answers, we realised that endless discussions about how we understand concepts of inclusion, homogenisation, exotisation and other notions may lead nowhere. Instead, we sought to translate these discussions into five senses: a sense of place, a sense of connection, a sense of generosity, a sense of multiplicity and a sense of break. So, the senses became the dramaturgy, the structure we wanted to use, the way to reflect the journey we had and the places we were coming from.

We have also been thinking of various ways to share our process as a prototype with the RESHAPE community and beyond. The group members decided to share the process through a virtual exhibition, inviting the viewers for a journey to different rooms named after different senses.

[LA] There was an idea during the Istanbul workshop about developing fiction, which is an interesting instrument in reflecting on the questions of your trajectory and exploring new possibilities. What happened with that?

[MK] It has been present mostly in the virtual exhibition framework, with different artworks we had in mind and which we used as an invitation to think otherwise. But we didn’t end up developing fiction per se, like a fictional institution, although that was one of the strong proposals within the group.

We thought of fiction as a tool to imagine otherwise, in order to get rid of the reality framework, at least for a while, and try to think of alternatives. A lot of colleagues keep telling me recently that fiction is what helped them to cope with harsh realities during the pandemic. I strongly believe fiction can help to reset the basic frameworks we operate in and can open up alternative structures.

[LA] Throughout this journey, what has reshaped for you? What are you taking away?

[MK] An enormous gratitude to have had the privilege of spending time with an absolutely unique constellation of people that I probably would have never met otherwise. A great lesson on how to listen to the unknown without having ready answers. And a feeling of solidarity, fragility, often coming back as a surprise, one that became possible in the midst of the pandemic, when the fear of isolation was haunting and nothing seemed familiar anymore.

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.